Many countries are now urging for diversification in manufacturing to insulate themselves against supply shocks in the future. While one method is to promote re-shoring and trade protectionism, this option is not so readily available to smaller economies. An alternative is signing free trade agreements with other manufacturing regions to incentivize shifting factories there. Who are the contenders to plug this gap?

____________________Note: This is meant to be a contemplative discussion piece on the future of emerging economies and their related stocks, not a prediction piece of its future price. In times as volatile as these, it is crucial to consider different sources and different views.

One economic consequence of the coronavirus pandemic was the disruption of global supply chains. Industries that were disproportionately reliant on Chinese manufacturing suffered the consequences in late March when quarantines led to the shutdown of factories located in mainland China. Many of the world’s leading electronic companies which relied on Chinese production for their hardware and components were forced to close retail outlets because they simply lacked the inventory to operate.

Foxconn, the renowned iPhone manufacturer, employed over a million workers in China. Their factories were forced to operate at 50% of seasonal capacity – delaying Apple’s production schedules. Hyundai’s automotive plants ceased to operate for five days, equivalent to losses of $500 million. This was simply because they lacked access to ‘wiring harnesses’ used to connect the vehicles’ complex electronics that were solely produced in China.

What these examples reveal is how highly integrated value chains are today. A disruption at one node could lead to bottlenecks further down the chain that compound upon themselves. Many countries are now urging for diversification in manufacturing to insulate themselves against supply shocks in the future. While one method is to promote reshoring and trade protectionism (looking at you, US…), this option is not so readily available to smaller economies. An alternative is signing free trade agreements with other manufacturing regions to incentivize shifting factories there.

Who are the contenders to plug this gap?

1. Vietnam

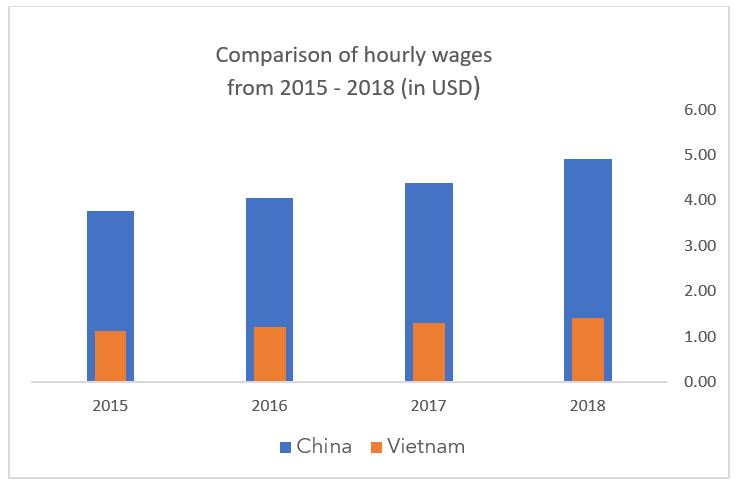

Since 2017, Vietnam was already labelled as an attractive destination for outsourcing manufacturing jobs. 70% of its population is of working age and this abundance of young, healthy labour has helped to suppress wage growth. In 2015, the average hourly wage for Vietnamese manufacturing was $1.12 USD. Chinese wages were $3.76; since then, the gap between the two wages has grown and Chinese workers are paid almost 3.5x more.

The appeal of low wages is strong, but the country has some challenges to address before it can fully develop into a global manufacturing hub. Vietnam has a total of just 2,600km of railways – 2% of China’s extensive network, and its road infrastructure is inadequate. Foreign companies must consider the nation’s ability to absorb increased manufacturing at the risk of traffic congestion and delays in their production and shipping schedules.

For investors seeking exposure to the Vietnamese stock market, the <u>VanEck Vectors Vietnam ETF (VNM:US)</u> is the most accessible opportunity for investors. Currently, the ETF is down 14% year-to-date although it has increased 30% in the past three months.

26% of the fund’s portfolio is concentrated in companies that do real estate investment; another bright spark is that 5.2% of the portfolio is concentrated in Mani Inc. – a medical equipment manufacturer. In 2018, 43% of the world’s medical supplies were made by China and the coronavirus outbreak highlighted concerns of national security when many countries were in shortage of key supplies like masks and ventilators.

2. Mexico

Mexico’s medical supply sector could also be set for significant expansion. It is the leading source of imported medical devices into the US. And with fractured tensions between China and US, the latter may be keen to turn towards its Latin American trading partner. Transport costs will be far cheaper than the ASEAN alternatives, and the country enjoys tariff-free access with the United States which remains the world’s largest importer.

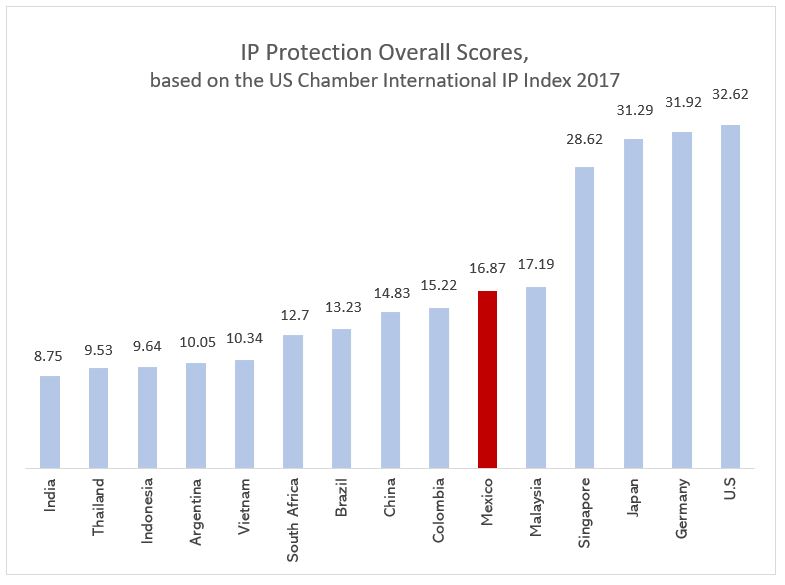

Of the emerging economies, Mexico ranks as one of the highest regarding intellectual property protection which should entice companies to set up manufacturing in the high-value goods industries.

Before the pandemic, Mexico’s aerospace industry was rapidly growing at approximately 14.4% per annum. One contributing factor was that the government had been investing in partnerships to stimulate innovation of home-grown technology and entrepreneurship within the aerospace sector. However, the pandemic will surely have delivered a sharp blow to this industry’s growth prospects as demand for air travel might be dampened for the next five years.

If you are looking for exposure to Mexico’s market, <u>The Mexico Fund (MXF:US)</u> is one option. Its portfolio consists of equities traded on the Mexican Stock Exchange with the two largest sectors being telecommunications and financial groups. Currently, the fund is trading at a discount of -11.87% to its net asset value; this implies that most investors are not optimistic about shares appreciating. But if Mexico’s economy lifts off, this could pay off.

3. Indonesia

Our final contender is Indonesia – a country whose decentralized government and poor policies have hampered its own economic potential. With a population of 273 million, it represents a vast domestic market that foreign companies should be elated to have access to. Its geographical position is also ideal for facilitating trade in Asia. Yet, the country is plagued with economic concerns – the combination of slowing GDP growth and a widening current account deficit is not what an emerging economy should be experiencing.

President Widodo’s government is planning to rely on the automotive, chemicals and electronics industry to boost manufacturing. It has introduced more aggressive tax holiday policies and reformed labour laws to attract foreign direct investment into the country. For exposure to the Indonesia market, the <u>iShares MSCI Indonesia ETF (NYSE:EIDO)</u> is a strong option. The fund pays out semi annual dividends of approximately 1% and a significant proportion of its portfolio is concentrated in financials and consumer staples. Of the three proposed ‘contenders’, Indonesia is perhaps the riskiest. Any growth prospects are solely predicated on its internal factors – whether its policies and economic strategy can exploit these advantages remains to be seen.

In conclusion, the pandemic has brought new opportunities in emerging economies. This article is not an investment guide but rather my thoughts on the economic situation. Pay attention to these economies and track those ETFs to stay on top of ways to grow your portfolio.